My name is Young.

I am the Chief Operation Officer for the Maiberger Institute. I’ve been working with Barb since 2010. Barb and I have also been married since 2012. In the time that Barb and I have been together, she has on occasion witnessed me introduce myself to new people both in-person (when that used to be a thing) and online — “Hi, my name is Young” — and then watch in dismay as the recipient of my greeting start to mispronounce my name, reverse my first and last name, feminize my name, Asianize the sound of my name, and mock my name, “Hey, even when you’re old, you’ll always be young.” And each time they butchered my name, Barb would notice the somatic responses in my body, my breathing, my neck, my jaw, and witness me putting on a stoic façade of politeness as if I’ve never heard that joke before, even though I was feeling a thousand papercuts on the inside every time it happened. Every time I met with someone — whether it was someone new or an old acquaintance — it created the potential for another opportunity for someone to dishonor my name, to mock my name, to dehumanize my name, and, in turn, dehumanize me through my name. And each time that happened, I experienced a thousand papercuts, every time, erasing my name from the conversation.

Every time I met a new student, a thousand papercuts. Every time I wrote my name on my homework, a thousand papercuts. Every time I filled out a college application, a thousand papercuts. Every time I filled out a form, a name tag, a job application. Whenever I was invited to holiday parties, family gatherings, or even happy hour, I often found myself feeling like a tourist visiting America, a disembodied observer witnessing customs, music, foods, languages, rituals and traditions completely foreign to me, while also acutely aware that I am the foreigner, I am the tourist, I am the one with the funny name.When someone I’ve already met multiple times still says my name incorrectly, it feels like a thousand papercuts on top of a thousand unhealed papercuts. Over time, through these internalized papercuts I experienced an unnamable pain whenever I met people.

I found myself dragging through the day, feeling sleepy all the time yet unable to sleep completely. Although it appeared as though I was going into hypo-arousal states possibly caused by a trauma response, trauma did not appear to tell the whole story. Although I felt a deep sadness, the word depression didn’t feel right. Although I was experiencing racism, calling my experiences racialized trauma didn’t fit either. I felt alone in my unnamable grief and pain. I lacked the understanding, context, and language to articulate or share my experiences with anyone, including my family and friends. For some Asians, sharing their experiences with like peers can be helpful, but in my particular case, I had no peers that I could trust. Asian people are We-people, Us-people. For Asian people, trying to heal without peers is like a thousand papercuts on top of a thousand unhealed papercuts. A thousand papercuts every day over a lifetime across GenerAsians of Living Ancestors is like a thousand unhealed traumas on top of a thousand unhealed traumas every day, and that’s just from my name.

When I was in my late 20’s, I finally had enough income (and health insurance) to seek out a therapist, but finding the right therapist was challenging. There was no such thing as Google Reviews to compare therapists, there was no such thing as Therapeasy to make it easy to find a therapist, there was no such thing as remote therapy over Zoom. I relied on the directory of therapists that my insurance provider had online, which had no Asian therapists listed. Colorado was not a therapy desert at the time, but it certainly was an Asian therapy desert. I decided to give a non-Asian therapist a try anyway, hoping that perhaps good therapy is just good therapy, and hoped that it wouldn’t matter whether the therapist was Asian; it mattered.

One therapist reversed my first name for my last name. Another therapist minimized my frustration of people mispronouncing my name by sharing how their experience with their own European sounding name was no big deal. One never took my personal history and just went straight into asking what positive and negative beliefs I had about myself. One time I had to spend half of my session with a therapist just trying to calmly explain that the “the look” I experienced whenever I walked into a non-Asian restaurant was not paranoia. One put me in a group where there were no other Asians, not one person that had any kind of lived experience remotely close to mine.

How could I trust a potential therapist would understand my lived experiences if they did not take the time to pronounce my name correctly? How could I trust my therapist if they had no context of my lived experience as an Asian person in this country?

I gave up on therapy.

I wandered around with a stoic façade for decades trying to name this pain and grief on my own, ferociously studying Asian culture and history, somatic psychology, media, racism, trauma, while also masking the thousands of spiritual papercuts I experienced on a daily basis.

Then in late 2019, I started hearing whispers of a virus coming out of Asia. I immediately thought, “Crap. This is going to be another Yellow Peril, this is going to be another G.R.I.D. all over again.” History has shown when there is disease, there is fear, and where there is fear, there is scapegoating. Where there is scapegoating, there is dehumanization, and where there is dehumanization, there is violence. Where there is violence, there is trauma. Long before quarantines, masks, social distancing, and even long before the hoarding, videos of Asians being attacked spiked in my Asian social feeds from all over the world at about the same rate and from the same places where this new yet-to-be-named virus was beginning to spread globally. I could tell where the virus was spreading by looking at the location of the Asiaphobia videos long before there was such a thing as a COVID map.

COVID driven Asiaphobia was spreading everywhere, and it made its way eventually to Colorado. I started to notice that each time I went to the grocery store, more and more strangers were giving me “the look,” a lot more than usual. They were looking at me as if I was the virus. Soon, I stopped going to the grocery store altogether. There was an instance when a woman began recording me with her mobile device without my consent, and stalked me all the way to my car, perhaps in hopes of creating some kind of viral confrontation video, or worse a viral police confrontation video. She yelled something about “deporting” or “reporting” me because of the “China virus.” She even told parents walking by, “Ya’ll wanna keep your kids away from that one,” while pointing directly at me. The worst part was that this happened in front of a Korean owned convenience shop I often frequented, a family run business I had to stop frequenting after that day, losing my one dose of Korean culture per day. I was being bullied out of my own culture, made invisible from my own people.

Then, Barb and I started to notice that the quality of food was always better when we ordered food for delivery under her name versus under my name, and these were our regular restaurants. Food became dangerous all of a sudden. Lyfts and Ubers became dangerous all of sudden. Filling up my car with gasoline became dangerous. Walking in the park became dangerous. Meanwhile, if one were to look on non-Asian social feeds, one would think non-Asians were not even aware these attacks on Asians were happening at all. It was as if Asians and non-Asians were living in two different bubbles of reality. Asian trauma was being made invisible.

As both COVID and Asiaphobia spread, the unnamable pain and grief within me amplified. I literally thought I was going insane. I lacked the context and the language to understand what was happening to me, let alone process any of it. I went into full hypo-arousal zombie mode for months, and, in many ways, I am still in zombie mode. I was going through the motions of life, but also felt disembodied from the world. I had to constantly remind myself to eat and drink water. I closed my eyes every night, but I never felt like I completely fell asleep. I was feeling pain and grief, but I could not figure out why. I was becoming more and more invisible from the world, and the world was becoming more and more invisible to me. It was not COVID that was doing this to me, it was Asiaphobia.

In the middle of all this, we, like most entrepreneurs, were also trying to contend with the pandemic, tending to our family and friends, pivoting our entire business model on the fly, while also trying to pay bills, get sleep, stay safe, stay healthy, and love each other. Thankfully, Barb and I worked hard over the past decade building our business on good fundamentals, good principals, and hiring good people so that our business could keep going even with me in full zombie mode. But we both knew it wouldn’t last. It was time for me to give therapy another try.

Thankfully, a lot changed in the 20 years since my last therapy sessions, and, with Barb’s help, we found exactly the type of therapist I needed: a therapist that understood my lived experience. Finding the right therapist literally saved me. It took nearly 20 years for me to finally give my pain and my grief a name, context. Therapy showed me that what I was experiencing was not insanity, but rather a traumatic response to the reality of what I was witnessing, an experience unique to Asians.

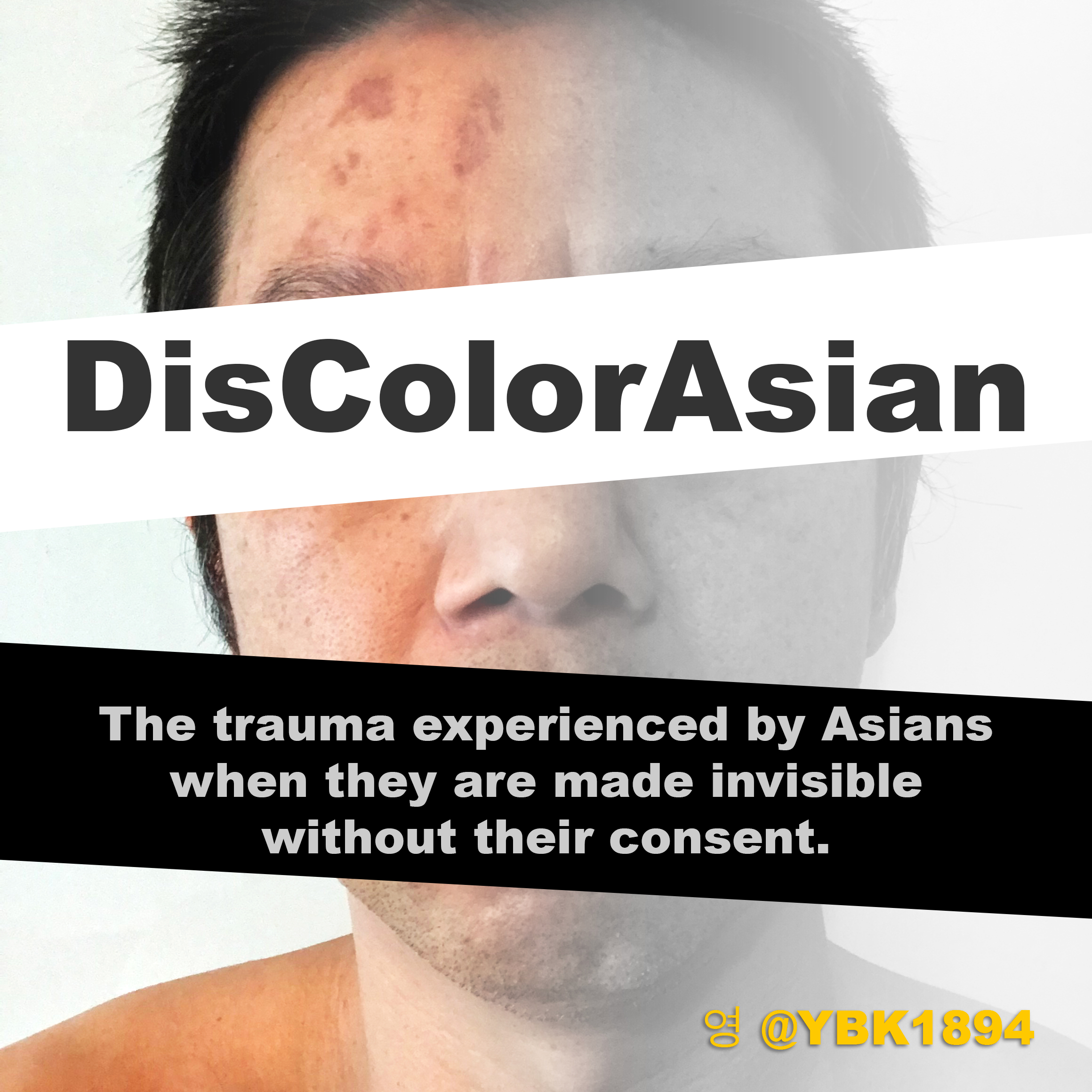

Through therapy I came to understand that I really was seeing two different reality bubbles. I was not imagining that. On my Asian social feeds all the photos of Asian family and friends were being taken indoors only, while on my non-Asian feeds I was seeing videos and selfies of my non-Asian friends showing off their privilege of being able to walk their dog or play with their children at the park without worrying about being attacked, spit on, or bullied just for looking Asian. While Asians were screaming to bring attention to the violence Asians were experiencing and witnessing, non-Asians were working on mastering the Floss on TikTok. I was not imagining this, I was not going insane, it was all really happening. What I was experiencing was not just trauma, not just vicarious trauma, not just depression, not just pain, not just grief, and not just racism. What I was experiencing is what I now call DisColorAsian.

DisColorAsian is the trauma experienced by Asians when they are made invisible without their consent. DisColoraAsian is when Asians are left out of conversations around race, politics, and culture. DisColorAsian is when Asians are forced to be adjacent to non-Asian politics without consent and without representation. DisColorAsian is when leaders, celebrities, influencers, and public figures of Asian descent self-identify as part-Asian or happens-to-be-part-Asian or and-Asian rather than as Asian+ or Asian-First or Asian-and. DisColorAsian is when a therapist, doctor, or nurse reverses your name on medical records. DisColorAsian is when Asians are made invisible by being clumped and discarded into a generic POC bin. DisColorAsian is when American shows, series, and movies use the word “ninja” in their titles yet they have nothing do with Japanese culture. DisColorAsian is when Asian singers on shows like “American Idol” or “The Voice” are told there is no genre of music, or musical “lane” for Asian voices. DisColorAsian is when Asian heroes are replaced by non-Asians. What chance does an Asian person or an Asian Family have of preserving their culture, their language, their traditions, their food, or planting their roots and feel grounded in America under the daily bombardment of these weapons of mass DisColorAsian trying to make Asians more and more invisible every day?

One recent example of DisColorAsian and its impact on Asian communities is when members of the Hollywood Foreign Press Association mispronounced “Minari.” The constant and persistent mispronunciation of “Minari” by the media is a way of whistle-dogging to the Asian community that Asian cinema is not sacred. They are saying the Asian American experience is not sacred, not worthy of representing the American dream. Can “Minari” be properly honored or recognized for its excellence in cinema against such weapons of mass DisColorAsian persistently mispronouncing its name to the public on a daily basis? The mispronunciation is so pervasive that even I have on occasion found myself mispronouncing “Minari.” Even Wonder Woman does not stand a chance against the onslaught of industrial DisColorAsian complex (1:20:36).

It would be easy to hold the presenters, hosts, and celebrities of award shows accountable for mispronouncing “Minari,” however, the responsibility inevitably belongs to the people hosting the party, the people in charge of putting together these award shows, like the HFPA. Organizations like the HFPA set every celebrity up for failure by not taking the time to make sure every presenter, host, journalists, celebrity, and guest at their events knew the proper pronunciation of the movies and the people they were presenting and interviewing. If a podcaster, an influencer, or a movie critic mispronounces “Minari,” can we really trust they watched the movie at all? If anyone wants to learn how to properly pronounce “Minari,” they just need to watch the movie, or listen to an interview with the director.

Can “Minari” be properly honored in the achievement of cinematically capturing the human experience of being a Korean in America if the people at the table making the decisions have never cooked Korean food, if they have never seen or felt or tasted 미나리, if they don’t know what kind of food these refugees of Eden are trying to grow on their little big garden, if they don’t know why the history of farming is sacred to Koreans, if they don’t understand the significance the word 이쁘다 in the movie. Korean food is sacred, Korean recipes are sacred, Korean medicine is sacred, Korean words are sacred.

Translations are sacred. Asian words are sacred. Asian names are sacred. Asian art is sacred. Can “Minari” be properly honored if the names of the people that helped bring little “Minari” to life are constantly mispronounced and misspelled? To mock, mispronounce, or misspell an Asian name, or to not take into account an Asian name’s country of origin is to dishonor that name and to dehumanize the steward of that name. Where there is dehumanization, there is violence, and where there is violence, there is trauma.

Just as I found Asiaphobia attack videos to be a good radar of how COVID was spreading, I have found that tracking how often the media mispronounces “Minari” as good radar of the invisible pervasiveness of hate crimes against Asians spreading across America. If the journalists of the HFPA cannot take the time properly pronounce the name of a movie at their own award show, can Asian communities really trust journalists with the stories and narratives of our Asian Elders, our Aunties, our Families, our Sisters & Brothers, our Living Ancestors, our Kin to be told with dignity and humanity, especially considering the media keep framing Asiaphobia as if it did not exist prior to COVID? Can Asian communities trust journalists will properly pronounce and spell the names of Asians that have been bullied, attacked, or killed if journalists cannot even pronounce “Minari” correctly? Can Asians really trust the CompStat on hate crimes against Asians if journalists refuse to print the word Asian in the headlines, and elected local law enforcement representatives refuse to recognize hate crimes against Asians? What else are journalists and elected local law enforcement representatives not categorizing as hate crimes? How can Asians defend themselves against hate crimes if journalists, leaders, and elected representatives of the law keep making hate crimes invisible? What color does the blood of our Asian Elders, our Families, our Kin need to be in order for journalists to deem Asian names worthy of being spelled and pronounced correctly? Whether it is the DisColorAsian of my name, the DisColorAsian of “Minari,” or the DisColorAsian of Asians that have been attacked, the impact of DisColorAsian is the same: dehumanization, violence, trauma.

Asians are sacred. The lived experiences of Asians are sacred. How Asians grieve is sacred. DisColorAsian may be similar to the experiences that other marginalized people may have experienced, yet it is also a uniquely Asian experience. DisColorAsian is the trauma Asian people feel when journalists leave out the Asian heritage of the victims that are killed from hate crimes. DisColorAsian is when journalists would rather say “worker” than “Asian” to describe a victim. DisColoraAsian is when elected local law enforcement representatives refuse to see crimes against Asians as hate crimes. DisColorAsian is when journalists misprint, misspell, mispronounce Asian names (whether that Asian is deceased or living), and in doing so they desecrate the names of our Elders, our Aunties, our Families, our Sisters & Brothers, our Living Ancestors, our Kin. DisColorAsian is when “they mispronounce our names, and then shame us for correcting them.” DisColorAsian is when journalists bury the names of our Elders, our Families, our Sisters & Brothers, our Living Ancestors, our Kin in an avalanche of other people’s agendas and other people’s politics, hijacking the public’s attention from these attacks against Asians under a deluge of terms like supremacy, guns, addiction, sex, mental illness, what-about-isms, what-if-isms, not-good-enough-isms, they will even talk about donkeys & elephants and use whatever other sound-bite they can to dilute and erase anything remotely resembling Asians from the headlines to the point everyone forgets this was about attacks against Asians in the first place. Every act of DisColorAsian makes Asians more invisible from the American conversation. Each act of DisColorAsian is a thousand papercuts every day, a thousand traumas every day.

Asians do not have the privilege of being considered Americans by default. Asians, by default, are considered immigrants, foreigners, and refugees. Asians are rarely, if ever considered American citizens as a default. Default-Americans have the privilege of having a seat at the table and determining who gets to be a part of the American conversation. I am not an influencer, I am not a politician, and I am not a public figure. I fight to bring my own chair to that same table not for myself but so that I may offer my seat to my Elders, to my Aunties, to my Living Ancestors, to my Family, to my Sisters & Brothers that have now joined the realm of our Living Ancestors, to my Kin whose voices have been drowned out by DisColorAsian. I bring my own chair to the table to give voice to those that do not have a voice. I bring my own chair to this conversation to help give voice to the collective grief and pain Asian people are feeling in a world that does not allow Asians to have a voice, a world that keeps Asian pain invisible, and, therefore, Asian resilience invisible.

To Default-Americans and the industrial DisColorAsian complex, Asia is considered a four-letter-word unfit to print, unworthy of being spoken. The language of Default-Americans fail to describe the trauma, pain, and grief of Asian communities because the language of Default-Americans is designed to systemically make Asians invisible, to hide Asian trauma, to hide Asian resilience, to hide Asian humanity. Default-Americans stigmatize the elderly, while Asians respect Elders. Default-Americans prefer individual servings, while Asians prefer family style. Default-Americans are obsessed with the word “self,” while Asians lean more toward Us-ness, We-ness, Our-ness. The language of Default-Americans is inadequate in describing the Asian experience in America. Trying to use Default-American paradigms to describe Asian bodymind experiences is like trying to use words of limited meaning to describe feelings of infinite meaning. The Default-American language is not built for the Asian bodymind. What Asian people need is their own language, their own words, their own framework to express their own grief and pain, and to better define and share their unique lived experiences as Asians in America, a language that belongs uniquely to Asians to describe Asian humanity.

My hope in sharing my own experiences with DisColorAsian is for Asian artists, writers, filmmakers, scholars, teachers, storytellers, and entrepreneurs — the modern 무 of this generation — to help Asian people explore and find their own ocean of meaning and context to what they are feeling with languages and concepts unique to the Asian experience, and unique to Asian expression. What Asians are experiencing is not just xenophobia and discrimination, it’s Asiaphobia and DiscriminAsian. What Asians are witnessing is not just cultural appropriation, it’s AppropriAsian. What Asian women are experiencing is not just misogyny, it’s MisogynAsian. What Asians are experiencing is not just racialized trauma, it’s TraumatizAsian. What Asian people are feeling is not just anger, grief, confusion, aloneness, vicarious trauma, and pain, it’s DisColorAsian.

Now, imagine the thousands of papercuts felt by every Asian person whenever they meet someone new, whenever they hear “Minari” mispronounced, whenever an Asian pereson sees the names of deceased Elders, Aunties, Sisters & Brothers, Families, Ancestors, their deceased Kin misspelled or mispronounced. Imagine every Asian person feeling those thousands of papercuts, every time, every day, a thousand traumas every day.

Now imagine one of those Asian people trying to find a therapist, hoping that the therapist might help them understand the pain of their lived experience, their unnamable grief. Then imagine what happens when this Asian person tries to introduce themselves to a therapist for the first time. Considering the persistence of the industrial DisColorAsian complex, what are the chances this Asian person would feel welcome, safe, validated, and witnessed by a therapist that has no clue about the lived experience of an Asian in America?

Therapy is sacred. Mental health professionals are invisible Essential Workers saving lives every day, Jedi superheroes healing the world in humble stealth. Therapy saved my life, literally. It took me nearly 20 years to find the right therapist, a therapist that could understand my lived experience, help me name my unique grief and pain, help me navigate the traumatic effects of DisColorAsian, how to start healing those papercuts, and reclaim what Asian resilience feels like. What helped was finding the right therapist, someone that could honor my lived experience as an Asian wandering through America. I do not want it to take 20 years for other Asians to find the right therapist. My hope is that therapists begin to see that the types of grief, pain, trauma, and racism Asian communities experience is uniquely Asian, and to be mindful of how Asians might be experiencing therapy.

To those struggling with the pain of DisColorAsian, I hope you find the courage to ask for help. Asking for help when you need it is self-care. Asking for help is sometimes the best way you can help yourself. For those seeking help, here is a list of resources to check out (I’ll keep adding to this list):

- Therapeasy (Colorado)

- Safehouse Progressive Alliance for Nonviolence (Colorado)

- Asians for Mental Health Directory

- Asian Mental Health Collective

- South Asian Therapists

- National Asian American Pacific Islander Mental Health Association

- Asian American Psychological Association

- Asian & Pacific Islander American Health Forum

- Asian American Health Initiative

- Mental Health America

- National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (800-273-8255)

- The Trevor Project (866-488-7386)

- National Domestic Violence Hotline (800-799-7233)

- Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network (800-656-4673)

- National Child Abuse Hotline (800-422-4453)

- Trans Lifeline (877-565-8860)

- Crisis Text Line (Text HOME to 741741 to connect with a Crisis Counselor)

- EMDR Therapist Directory

- EMDRIA.org

I also highly recommend reading “Permission to Come Home: Reclaiming Mental Health as Asian Americans” by Jenny T. Want, PhD, the founder of Asians for Mental Health Directory.

For me, all Asians are sacred, and all Asians are my Family, all Asians are my Kin. As an Asian person, no matter where I am in the world, I cannot help but sense a deep We-ness, a deep Us-ness, a deep Our-ness embedded and hardwired into my bodymind, my DNA, my soul. For me, whenever I hear, read, or witness an Asian person in pain, I feel it, long before I ever learn their names. I feel it because we are all Family, we are all Kin, we are all walking with our Living Ancestors.

Whenever I find myself unable to name or process the grief and pain of our Asian Elders, our Families, our Kin, I turn towards 살풀이, a spiritual cleansing dance. I find that cinema, music, and dance have ways of expressing and exploring feelings that are difficult to name. 살풀이 teaches me that grief — just like cinema, music, and dance — is about movement, a deeply personal and sacred movement. As I watch the delicate movements, and feel the music crying, I can feel my papercuts healing throughout my bodymind. The dance teaches me that working through pain, grief, and trauma is a life-long process, a life-long sacred movement of patience and compassion. I share this dance with you, my fellow wanderers, orphaned souls, my fellow refugees of DisColorAsian that are struggling to put into words what you are feeling, struggling to process your unique pain, your unique grief. Asian grief is sacred. Your grief is sacred, and how you choose to move through your grief is sacred. I hope this dance helps you find your own sacred movement.

Please take care, be safe, and stay healthy.

Thank you for your consideration.

My name is 영